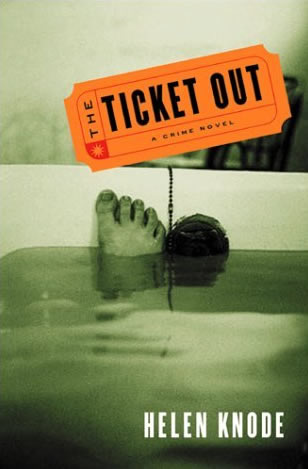

The Ticket Out

A Crime Novel

Ann Whitehead is sick of her job. She’s a movie critic for a counterculture rag in Los Angeles and she needs a break badly. Instead of a break, she gets a murder. A woman dies in Ann’s bathtub: the victim is a film school grad and industry hopeful. It’s the kind of story Ann was born to write, but the disgraced LAPD detective leading the investigation is determined to stop her.

The search for the killer turns into a search for the victim’s missing script, the story of another woman murdered in 1944. Suddenly there are two killers and what seems to be a complicated conspiracy spanning decades. Ann is smack in the middle and everyone she meets wants into the film business — whatever the price.

There’s never been a thriller hitched as brilliantly to the new underbelly of Hollywood as this one. Helen Knode is a startling and original voice.

Excerpt from The Ticket Out

[From Chapter 1]

The movie lost me way early on. I sighed, uncrossed my legs, and stuck them in the aisle. Mark poked me. He whispered, “Stop it. Sit still.”

I said, “If this tuna doesn’t end soon, I’m going to shoot myself.”

Mark patted my arm. I pictured the gun I kept in a closet at home, and laughed out loud.

Someone said, “Sssh!” Two people in the row ahead of us turned around.

I bit my lip and slumped down lower. The theater was packed with journalists. A new Tom Cruise movie was always an event and the studio had put us in their largest screening room. I picked the major critics out of the crowd and tried to guess what they were thinking. Their faces were blank, of course: their jobs were too political for them to let their real feelings show. But I could guess what the feature writers were thinking. They were worried how much time they’d have with Cruise and how much space they’d get after the photo spread. They had no choice about the movie; they had to be nice. Sometimes I envied them.

I sighed again. Mark reached over and tapped my notebook with his pen. He whispered, “Write.”

“Can’t I please go?”

Mark pointed at my notebook. I flipped to a new page and looked up at the screen. Tom Cruise was kissing Penelope Cruz on a background of dark bedsheets. He dabbed at her mouth while the camera and music tried to make it sexy.

I stopped myself from laughing again. I’d never bought Cruise as a romantic hero. The film could be set in the nineteenth century or cyberspace; it didn’t matter. He was a plastic corporate doll. He made love like a guy who’d answer to CEOs if he mixed his bodily fluid with the costar’s.

I shut my notebook and started to get up. Mark looked over. I whispered, “I’ll be right back.”

He nodded and I walked up the aisle to the lobby. Out in the light I checked the press kit for a running time. The movie still had an hour left. I found an upholstered bench, lay down, and closed my eyes. There was the rest of this screening, then Barry’s party tonight. I didn’t want to go to his useless party. I wanted to be alone to think.

Something was very wrong with me. I’d been acting unprofessional and I couldn’t figure out why. Over the past month I’d missed a deadline and refused to write about the fall season. I just couldn’t get enthusiastic about Harry Potter — or even a new David Lynch film. It wasn’t normal. The summer movies were bad, but low morale was no excuse. There’d been bad periods before and I didn’t miss deadlines or fight Mark’s assignments. No one had said anything at the paper yet. But there were hints that I might be in trouble.

If I was in trouble, I knew Mark would take my side. I didn’t know, though, if Mark could protect me from our boss. Barry’s attitude about Hollywood had changed. He’d softened up toward the studios and started to interfere in the film section; he said he wanted our coverage to be more “mainstream.” Mark and I were having a hard time believing it. On every other topic, the L.A. Millennium was raucously un-mainstream: we couldn’t believe that Barry Melling would cave in to Hollywood. We also knew that the pressure to cave was tremendous and that Barry wouldn’t be the first or last casualty.

I’d felt the pressure myself when I moved to L.A. I knew that Hollywood was a company town, but I didn’t know what that meant for me as a critic. I’d gotten the picture fast. The Millennium was a hip local weekly — close to the bottom of the clout barrel by Industry standards. Our opinion might affect the fate of an independent or foreign film, but we couldn’t hope to affect the opening weekend of a studio movie. Which meant, among other things, that we weren’t on the list for early Tom Cruise previews. Tonight was a total surprise. Barry had exerted himself to arrange this screening. He’d made phone calls and twisted arms and somehow gotten Mark and me in.

Mark didn’t know what Barry was planning. He feared what I feared: that Barry wanted Cruise for the cover. We both thought that was impossible. The Millennium hardly ever got access to Hollywood stars, and never a star as big as Cruise. But Barry just might swing an interview, and if he did, I might be forced to contribute. I might not be in a position to refuse.

Someone touched my shoulder. I opened my eyes. Mark was standing over me. He said, “It’s been fifteen minutes.”

I rolled off the bench and followed him back into the theater.

This was the best job I could ever imagine. I loved movies — and all I did was see movies, think about movies, and write about movies. They let me say what I wanted and I earned decent money doing it.

But I opened my notebook, looked up at Tom Cruise, and felt profoundly tired.